Now Reading: Will India suspending Indus Waters Treaty have an effect on Pakistan?

-

01

Will India suspending Indus Waters Treaty have an effect on Pakistan?

Will India suspending Indus Waters Treaty have an effect on Pakistan?

Setting correspondent, BBC World Service

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesWill India have the ability to cease the Indus river and two of its tributaries from flowing into Pakistan?

That is the query on many minds, after India suspended a serious treaty governing water sharing of six rivers within the Indus basin between the 2 international locations, following Tuesday’s horrific assault in Indian-administered Kashmir.

The 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) survived two wars between the nuclear rivals and was seen for instance of trans-boundary water administration.

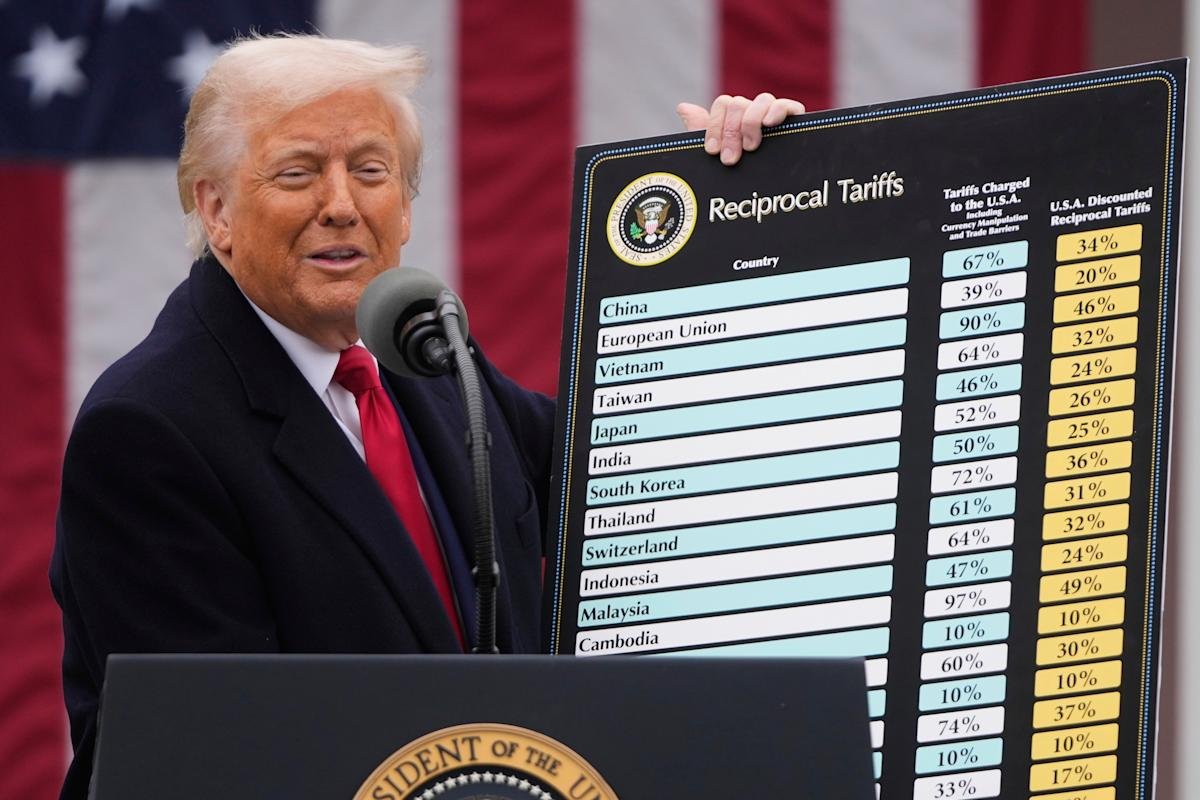

The suspension is amongst a number of steps India has taken towards Pakistan, accusing it of backing cross-border terrorism – a cost Islamabad flatly denies. It has additionally hit again with reciprocal measures towards Delhi, and stated stopping water circulate “shall be thought of as an Act of Struggle”.

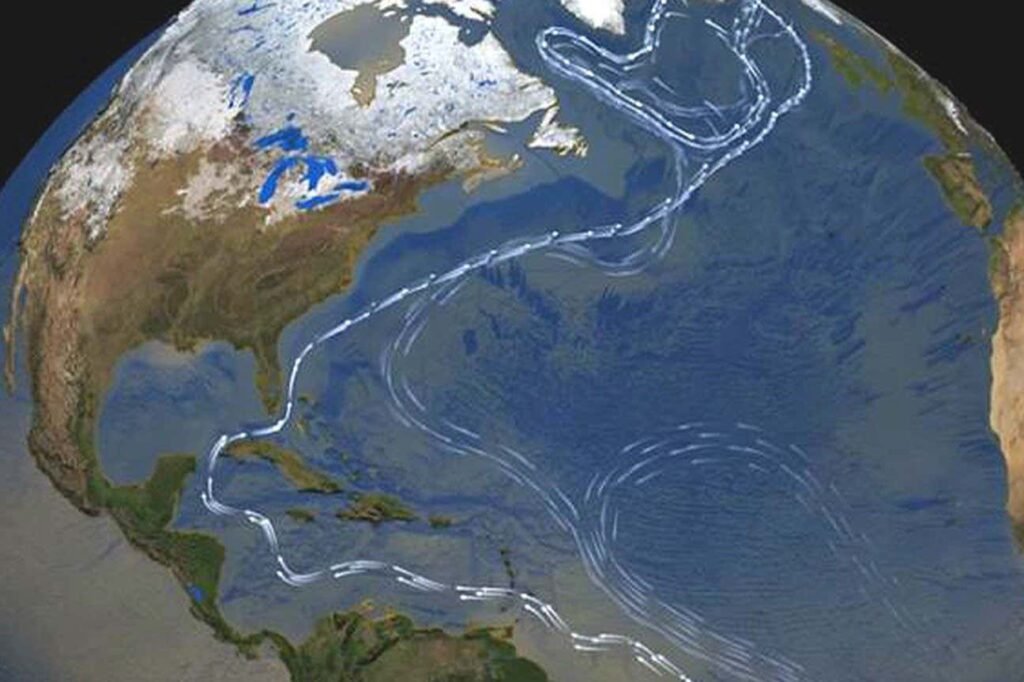

The treaty allotted the three jap rivers – the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej – of the Indus basin to India, whereas 80% of the three western ones – the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab – to Pakistan.

Disputes have flared previously, with Pakistan objecting to a few of India’s hydropower and water infrastructure tasks, arguing they would cut back river flows and violate the treaty. (Greater than 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture and round a 3rd of its hydropower rely upon the Indus basin’s water.)

EPA

EPAIndia, in the meantime, has been pushing to overview and modify the treaty, citing altering wants – from irrigation and consuming water to hydropower – in mild of things like local weather change.

Through the years, Pakistan and India have pursued competing authorized avenues beneath the treaty brokered by the World Financial institution.

However that is the primary time both aspect has introduced a suspension – and notably, it is the upstream nation, India, giving it a geographic benefit.

However what does the suspension actually imply? May India maintain again or divert the Indus basin’s waters, depriving Pakistan of its lifeline? And is it even able to doing so?

Specialists say it is practically unattainable for India to carry again tens of billions of cubic metres of water from the western rivers throughout high-flow intervals. It lacks each the large storage infrastructure and the intensive canals wanted to divert such volumes.

“The infrastructure India has are principally run-of-the-river hydropower crops that don’t want huge storage,” stated Himanshu Thakkar, a regional water assets professional with the South Asia Community on Dams, Rivers and Folks.

Such hydropower crops use the pressure of operating water to spin generators and generate electrical energy, with out holding again giant volumes of water.

Indian specialists say insufficient infrastructure has stored India from absolutely utilising even its 20% share of the Jhelum, Chenab and Indus waters beneath the treaty – a key purpose they argue for constructing storage buildings, which Pakistan opposes citing treaty provisions.

Specialists say India can now modify current infrastructure or construct new ones to carry again or divert extra water with out informing Pakistan.

“In contrast to previously, India will no longer be required to share its mission paperwork with Pakistan,” stated Mr Thakkar.

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesHowever challenges like troublesome terrain and protests inside India itself over a few of its tasks have meant that building of water infrastructure within the Indus basin has not moved quick sufficient.

After a militant assault in Indian-administered Kashmir in 2016, Indian water assets ministry officers had instructed the BBC they’d velocity up building of a number of dams and water storage tasks within the Indus basin.

Though there is no such thing as a official data on the standing of such tasks, sources say progress has been restricted.

Some specialists say that if India begins controlling the circulate with its current and potential infrastructure, Pakistan might really feel the affect throughout the dry season, when water availability is already at its lowest.

“A extra urgent concern is what occurs within the dry season – when the flows throughout the basin are decrease, storage issues extra, and timing turns into extra vital,” Hassan F Khan, assistant professor of City Environmental Coverage and Environmental Research at Tufts College, wrote within the Daybreak newspaper.

“That’s the place the absence of treaty constraints might begin to be felt extra acutely.”

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesThe treaty requires India to share hydrological information with Pakistan – essential for flood forecasting and planning for irrigation, hydropower and consuming water.

Pradeep Kumar Saxena, India’s former IWT commissioner for over six years, instructed the Press Belief of India information company that the nation can now cease sharing flood information with Pakistan.

The area sees damaging floods throughout the monsoon season, which begins in June and lasts till September. However Pakistani authorities have stated India was already sharing very restricted hydrological information.

“India was sharing solely round 40% of the information even earlier than it made the most recent announcement,” Shiraz Memon, Pakistan’s former further commissioner of the Indus Waters Treaty, instructed BBC Urdu.

One other difficulty that comes up every time there’s water-related pressure within the area is that if the upstream nation can “weaponise” water towards the downstream nation.

That is typically known as a “water bomb”, the place the upstream nation can quickly maintain again water after which launch it all of the sudden, with out warning, inflicting huge injury downstream.

May India try this?

Specialists say India would first danger flooding its personal territory as its dams are removed from the Pakistan border. Nevertheless, it might now flush silt from its reservoirs with out prior warning – doubtlessly inflicting injury downstream in Pakistan.

Himalayan rivers just like the Indus carry excessive silt ranges, which shortly accumulate in dams and barrages. Sudden flushing of this silt could cause important downstream injury.

There is a larger image: India is downstream of China within the Brahmaputra basin, and the Indus originates in Tibet.

In 2016, after India warned that “blood and water can’t circulate collectively” following a militant assault in Indian-administered Kashmir which India blamed on Pakistan, China blocked a tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo – that turns into the Brahmaputra in northeast India.

China, that has Pakistan as its ally, stated that they had executed it because it was wanted for a hydropower mission they have been constructing close to the border. However the timing of the transfer was seen as Beijing coming in to assist Islamabad.

After constructing a number of hydropower crops in Tibet, China has green-lit what would be the world’s largest dam on the decrease reaches of Yarlung Tsangpo.

Beijing claims minimal environmental affect, however India fears it might give China important management over the river’s circulate.