Now Reading: Former federal worker elected to New Jersey local office

-

01

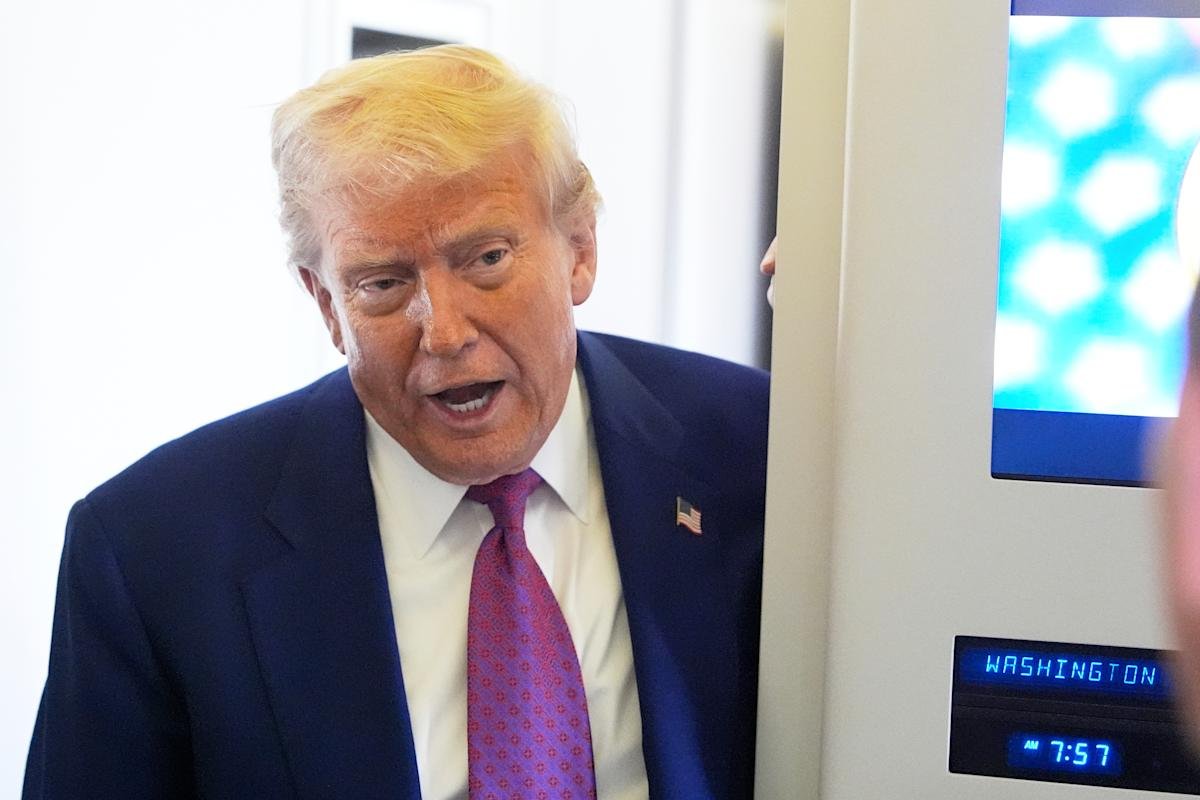

Former federal worker elected to New Jersey local office

Former federal worker elected to New Jersey local office

About four months after resigning from the federal agency Trump rebranded as the U.S. DOGE Service, this NJ resident won local office by 49 votes.

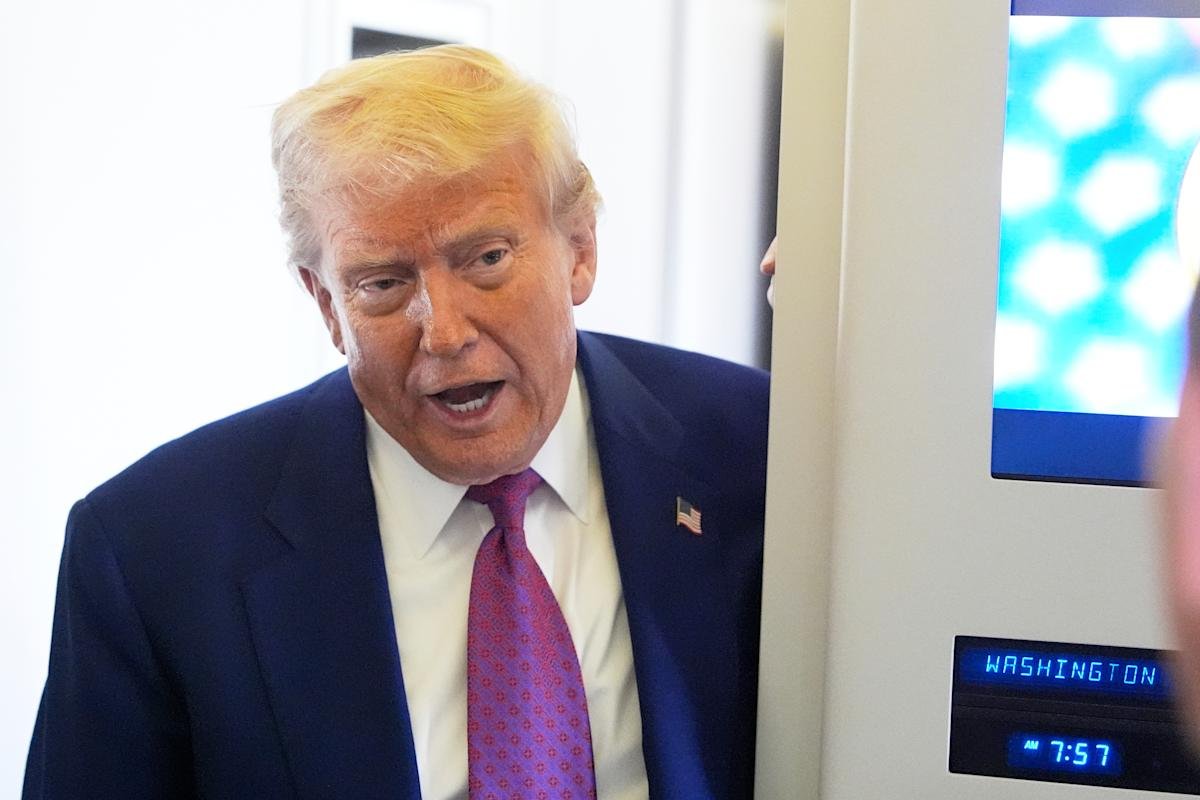

How did Elon Musk become so powerful in Washington?

As leader of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Elon Musk has made major changes, but who is Elon Musk and how did he rise in Washington?

Itir Cole tried to take some time off after quitting her job with the federal government early in the Trump administration.

“I tried to read books, I tried to watch Netflix. But a day or two of that, and I was like, okay, I’m good. Now, what?” Cole, 40, told USA TODAY.

Then her husband mentioned offhand that there was an open seat on her New Jersey town’s governing body. No one her age or with her life experience was planning to make a bid for the nonpartisan Haddonfield Borough Commission.

So she did.

Cole won her mid-May race by 49 votes, about four months after resigning from the U.S. Digital Service ‒ the federal agency President Donald Trump and entrepreneur Elon Musk rebranded as the United States DOGE Service. A ceremonial swearing in was held May 27.

Her victory places her at the forefront of a flood of federal workers looking to run for public office. Many say they want to continue serving Americans after leaving the government either voluntarily or through mass layoffs, as Trump dramatically downsizes the federal workforce.

Why she left her government job

Cole said her year-and-a-half in the federal government was a pivot point in her life. She had spent most of her career working in product management and building health care software for private companies.

“The federal government felt like it hit all my check boxes,” she said. “I can make a living. I feel good about what I’m doing every day. I’m contributing to the wellness of my community, my nation, and it’s something when I look back on, I’m going to feel really proud of having contributed to even as a small part of it.”

U.S. Digital Service employees were detailed to other agencies to help fix or monitor high priority tech projects. Cole worked with the Centers for Disease Control to improve a cross state infectious disease surveillance system after the COVID-19 pandemic.

But the arrival of DOGE employees on Inauguration Day transformed the nonpartisan tech agency, Cole said.

“The job changed pretty much overnight,” she said.

All employees were interviewed with questions she said felt like were asking about loyalty to the new administration. She had been hired as a remote employee, but there was talk of requiring a return to the office. The “fork in the road” email that told federal employees to either get on board with the sweeping changes or leave was the last straw, she said.

The White House press office did not respond to a request for comment.

Cole quickly chose to resign, as did others. On Feb. 14, her last day, the remaining 40 or so members of her team were fired, she said.

‘Okay, I will do it’

When she first looked at the Haddonfield Borough Commission race, Cole said she was alarmed that none of the candidates represented the so-called sandwich generation: people with both young kids at home and elderly parents to take care of.

She implored friends to run, offering to act as their campaign manager and organize their campaign events, but no one had the time.

“I couldn’t let go of the fact that … there’s no woman with a young family juggling responsibilities of professional life and family life. No one from our phase is going to be there, and there are going to be decisions made that are not in the best interest of the entire community,” Cole said. “So I thought, Okay, I will do it.”

Cole had to move quickly to get on the ballot in her suburban town of 12,500, not far from Philadelphia.

She pulled together 100 signed petitions in 3 days ‒ twice the number she needed. There was no time to build a coalition of supporters or get backing from candidate recruitment groups that mentor new candidates and that are getting inundated with requests for help from former federal employees.

She had to just wing it.

Cole said she started with a handful of regulars she knew at her local coffee shop, then a dozen or so moms she knew from school drop off. The former head of the local soccer leagues sat down with her and made introductions to the Lions Club, the Rotary Club and various nonprofits. Soon people offered to host house parties to introduce her to their neighborhood.

“I accepted every invite, and I put myself out there as much as I could,” she said.

Campaigning as an introvert was painful, Cole said. It helped that the position is non-partisan and she could focus on local issues like affordable housing, crowded schools and new soccer fields.

The part-time commissioner job pays $6,000 a year, which Cole said she expects to mostly go toward expenses related to the role. She’s still looking for a full time job.

Cole said she hasn’t given much thought to a political future. She doesn’t intend to hold the position past a single four-year term, saying she thinks the post should rotate among community members.

“What I’m going to spend the next four years doing is making sure that people see this as a very doable job, that it hopefully encourages others to be like, Oh, she can do it. I can probably do it too,” she said.