Now Reading: The U.S. sold this tribe’s land illegally. It’s now the latest Native group to get its home back | KCUR

-

01

The U.S. sold this tribe’s land illegally. It’s now the latest Native group to get its home back | KCUR

The U.S. sold this tribe’s land illegally. It’s now the latest Native group to get its home back | KCUR

There are more than 500 miles between the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation’s tribal reservation in northeastern Kansas and 1,500 acres of mostly prairie in northern Illinois.

So, Raphael Wahwassuck has come far to visit the site of a long-gone cabin there. Except it’s not an unfamiliar place to him and his kin. Wahwassuck is a member of the Prairie Band’s tribal council and a direct descendant of Chief Shab-eh-nay, for whom the state park is named after.

“If this is accurate — that this was the site where his cabin was — then, within a few 100 yards, I’ve got some family members that are buried out in these woods,” Wahwassuck said.

Most of the tribe were forced from their homelands of the Great Lakes region into Kansas. They ceded approximately 28 million acres to the United States government, while an 1829 treaty promised Chief Shab-eh-nay 1,280 acres of reservation in Illinois.

Yet when he left to visit his relatives in Kansas, the U.S. sold the chief’s land, illegally, to white settlers in 1849.

Peter Medlin

/

Courtesy of the DeKalb County History Center

Much of it has since been developed into residential properties, a golf course, or is maintained by state and county governments as park land. The tribal nation, meanwhile, is now headquartered in the Kansas town of Mayetta. Despite this, Wahwassuck said the Prairie Band has remained connected to their ancestral home to this day.

“Every generation of our family have returned to Illinois at some point,” he said. “To these lands, to this site, to visit and to have that continued presence in the area.”

Over the last 15 years, the tribe has spent $10 million to purchase parts of the original reservation — including 130 acres near Shabbona Lake State Park in what is now DeKalb County, Illinois.

In 2024, the U.S. Department of the Interior placed the tribe’s Illinois land into trust — making the Prairie Band the first federally-recognized tribal nation in the state. In March, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed a bill into law that transferred ownership of the chief’s namesake park to the tribe. For now, the Prairie Band plans to work with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources to keep Shabbona Lake maintained and opened to the public.

For Wahwassuck, this return is a step towards “correcting some of the historical injustices” his tribe has experienced.

“There’s a lot of emotion behind that,” he said. “To see that happen in my lifetime is something that I thought I would never experience.”

Stories like the Prairie Band’s — of being forced to relinquish their lands and having a treaty broken — are common throughout American history. Today, there’s a growing movement of tribes reclaiming their ancestral lands that some scholars and advocates have called “Land Back.”

Across the Midwest and Great Plains, many tribes have done this by purchasing land outright, petitioning the state and federal government for its return, or partnering with local organizations that are willing to give it back.

Recent examples of tribes getting land back include the Upper Sioux Community, which had two square miles of sacred land returned to them last year by the state of Minnesota long after the tribe’s exile in 1862. An act of Congress returned 1,600 acres to the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska last summer, more than 50 years after it was seized by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Osage Nation, which was forcibly removed from Missouri to Oklahoma, took ownership last December of the last remaining Native mound in St. Louis.

Peter Medlin

/

Harvest Public Media

How and why land comes back

There’s nothing new about the Land Back movement, according to Kevin Washburn.

“Tribes have been wanting their land back probably since before the ink was dried on the original treaties where they ceded that land,” he said.

Washburn, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation, previously served as assistant secretary of Indian Affairs during President Barack Obama’s administration and is a former dean of the University of Iowa’s College of Law.

He says the “bait and switch” the Prairie Band experienced in the 1800s was not uncommon, and tribes had little legal recourse in the court systems back then.

“There was a lot of wrongfulness that happened in the taking of Indian lands,” said Washburn. “Nearly every tribe — something was not kosher about the way the process happened.”

National Archives

/

National Archives

Tribes, including the Prairie Band, have gotten some of their ancestral home back from the state or federal government, but that’s not the norm, according to Washburn. If a tribe wants their land back, especially when they’re located in another state, he said there’s a price to pay.

“The most common way that tribes get land back is they go out and buy the land,” Washburn said.

While it’s possible for tribes to purchase land anywhere, the challenge is getting the U.S. to take that land into trust and then treat it like a reservation, according to Washburn.

“They have to convince the federal government that there’s good reason to do so,” he said. “That usually involves some historical or cultural tie to that land. So there’s limitations on doing this. It’s not a free-for-all.”

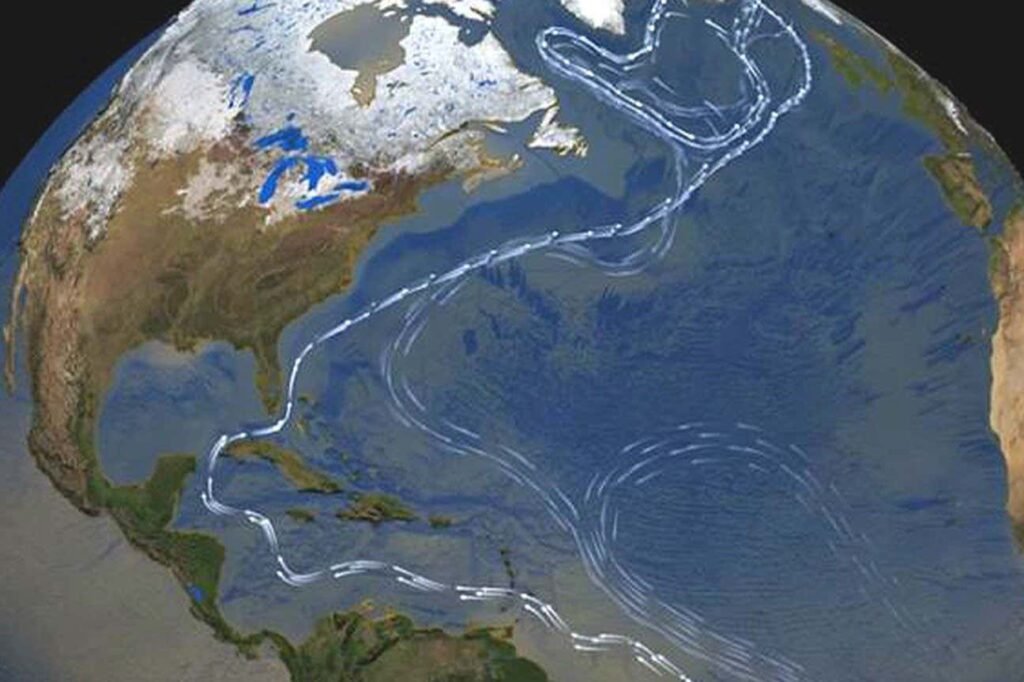

Over the past 300 years, European and American settlers have caused tribes to lose about 98.9% of their land due to forced migration and dispossession, according to a 2021 report. Today, Native tribes and individuals own close to 60 million acres of land — about the size of the state of Oregon — in trust across the country, according to the Department of the Interior.

There were decades where many tribes did not own any land, according to Nicole Rummel of the Oneida Nation’s land management department. Her tribe is just outside of Green Bay, Wisconsin.

The Oneida’s original reservation was around 65,000 acres, but when the Dawes Act passed in 1887, it broke commonly-owned reservations into individual land parcels and auctioned off the rest. Like many other tribal nations, it was devastating for the Oneida, said Rummel.

Courtesy of Oneida Nation Farm

“Pretty much all of the land was gone from the tribal members in 25 years,” she said. “That’s how long it took for our 65,000 acres to be sold to non-members.”

In the century since “allotment” ended, the Oneida has purchased nearly half of that reservation that was lost, according to Rummel. That was made possible by the tribe’s land commission, which was formed in 1941 when there was only about 1,900 acres under their control.

In 1982, the Oneida tribe approved a 30 cent tax on every sale of cigarette cartons, which would be set aside for land acquisition. Then in 1988, Rummel said the tribe’s gaming operations helped push things even further.

“So right now we own 26,000 acres,” she said. “We’re almost halfway there.”

Over the past decade, the tribe has established the Oneida Nation Farm, which has allowed them to lease about 6,000 acres so that tribal members can grow their own food, such as corn, beans, and squash, famously known as “the three sisters.” She said the Oneida also operates its very own buffalo and cattle ranch through it’s agriculture department, which has helped boost the tribe’s economic development.

“We wouldn’t be able to do any of that if we didn’t purchase the land first,” Rummel said.

Bumps in the road

Matthew Wesaw is the tribal chair of the Pokagon Band of the Potawatomi. Over the years, he has sometimes noticed a pattern when the tribe sought to buy land. Their land-use board would research the traditional site of a former village, the home of a tribal leader or burial ground. Then they’d make an effort to purchase it, he said, but the price tag often changed.

“One of the biggest difficulties is when people find out it’s the Pokagon that’s looking to purchase the land. The price gets really jacked up,” he said. “So, we have to deal with that. We have to do a lot of stuff under the cover of different entities.”

Their tribe’s reservation is primarily located in southwestern Michigan, but northern Indiana is home too. In 2016, they became Indiana’s first federally-recognized tribe when 166 acres the tribe owns near South Bend were placed into trust.

The tribe operates a real estate company, according to Wesaw, which helps the Pokagon purchase land without tipping sellers off that the land is of special significance. Other times, the tribe has encountered sellers who act in good faith, he said, so they can be upfront about the land purchases and how it will help the tribe.

“Sometimes we let people know who we are and what we’re about,” Wesaw said. “It’s all about benefiting our people, getting them healthy, getting them educated, getting good houses.”

Courtesy of the Pokagon Band of the Potawatomi

The journey hasn’t always been easy, said Wesaw. Even with a long documented history, like tribal council meetings recorded as far back as the 1800s, the tribe has done much of the work on its own. Wesaw said they’ve spent years trying to build relationships with former governors, attorney generals and other officials in Indiana.

So, the term “Land Back” is challenging for Wesaw.

“That really doesn’t tell the proper story, because none of our land has been returned. We’ve had to go back and buy it,” he said.

The road is “a little bumpy sometimes,” said Wesaw, but it’s worth doing for the tribe.

“You’re always working for seven generations ahead,” he said. “And when you look back seven generations, those people were working for what we’ve got today. And we need to keep doing that.”

There can be other difficulties for tribes, as well. That includes local governments concerned about losing tax revenue, particularly in the Midwest where many tribal lands were developed decades ago.

The U.S. federal government placed 500 acres into trust for the Oneida Nation in 2023. Then a Wisconsin village sued, claiming the process was biased and that the lost tax revenue would severely impact their economy. For now, the future of that Oneida land is up in the air, while the Department of the Interior defends their decision in federal court.

“I think a lot of the nations try to have good relationships with the local municipalities. Obviously, we have to work together. We live in the same space, and we do try,” said Rummel. “There are times when those relationships don’t work out as best as they could, and yes that can extend that process.”

The Prairie Band won’t have to worry about their recent land transfer from Illinois, according to Wahwassuck. Since it was owned by the state, Shabbona Lake State Park is not on county tax rolls.

The future of land back

In April, the University of Kansas hosted the Great Plains LandBack Leadership Summit. Experts and leaders from the Oglala Lakota, Ojibwe, and Osage, among other tribes, gathered alongside non-Natives as well to discuss the challenges and successes that tribes have experienced with reclaiming land.

Courtesy of the University of Kansas

“These issues are really complex and the more that we’re in community with each other, the more we can talk about the hard parts, the more we can talk about the lessons we’ve learned,” said Ward Lyles, a professor of Urban Planning and Indigenous Studies who helped organize the summit.

The University of Kansas also has a free online database that maps the Land Back movement, created by Lyles and law professor Sarah Deer, a citizen of the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma. The researchers have cataloged at least 100 land transfers in over 30 U.S. states and Canadian provinces. They focus on federal, state and non-profit land transfers to tribes, rather than instances of tribes buying land outright.

“We wanted, first and foremost, to represent that this movement is alive and well and appears to be growing,” Lyles said.

The research team last updated the map at the end of 2023, but Lyles said they hope to launch a new version eventually. For now, he said they’ll continue to track down each land transfer as they come.

Lyles, who is not Native, said it’s crucial to prioritize the voices of tribal communities. These kinds of events and projects, he said, help all people to understand the Land Back movement — especially in the face of climate change and increasing weather hazards.

“Land and water are the source of all life,” he said. “We have to be in better relationship with the land.”

Although tribes face some opposition in getting land back, Washburn, the former assistant secretary at the Department of the Interior, said it’s not been a partisan issue.

Over the past few decades, he said, tribal lands have been restored under both Democratic and Republican administrations. That largely began, he said, with the Indian Reorganization Act — which was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934.

“The law that allows that has been on the books the entire time. And so a lot of tribes have been working at it for a long time,” Washburn said.

During his time with the Obama administration, Washburn said that tribes saw an estimated 562,000 acres of land restored around the country. And that hasn’t stopped in the proceeding years either, as some 3 million acres of land was returned to tribes at the end of the decade-long federal “Land Buy-Back” program in 2023.

“The Biden administration did several hundred thousand acres. Heck, the last Trump administration did a fair amount of land into trust. It wasn’t as much as Obama or Biden, but it happens in Republican administrations and Democrat administrations,” he said.

The Land Back movement has grown both over the past century, and Washburn said he doesn’t expect it to slow down.

“Lots of people want to see tribes restored or at least some of these wrongs addressed,” he said.

Throughout the 1800s, Washburn’s tribe of the Chickasaw Nation was forcibly removed from what is now the Memphis, Tennessee-area into Oklahoma. That was disruptive, he said, but the tribe, including his mother, still return once a year to feel a sense of belonging. And that’s a feeling, he said, that many others can relate to.

“Most Americans are deeply embedded in their home and their communities, but it’s even more so for tribes,” said Washburn.

For tribal chairman Wesaw, the future of his tribe and its health goes hand-in-hand with their ancestral home in Indiana. He said they once visited the Oneida’s land in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where the tribe has its own cattle ranch. One day, said Wesaw, the Pokagon Band hopes to convert some of their land into organic farming.

“There’s no more land being made,” Wesaw said. “So the more we can control, the more that we can have that is purposeful for our culture and traditions, is good.”

Peter Medlin

/

Harvest Public Media

Back in Illinois, Wahwassuck is happy that much of Chief Shab-eh-nay’s land has finally been returned, and that his tribe’s sovereignty has been reaffirmed. But the return hasn’t changed his relationship with this land, he said.

To him and his family, it’s always been home.

“I didn’t need the piece of paper to really drive that home, because that’s something that has been instilled in me since I was a young boy.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.