Now Reading: Trump’s Playbook to Cripple “60 Minutes” and the Press

-

01

Trump’s Playbook to Cripple “60 Minutes” and the Press

Trump’s Playbook to Cripple “60 Minutes” and the Press

Listen and subscribe: Apple | Spotify | Google | Wherever You Listen

Sign up for our daily newsletter to get the best of The New Yorker in your inbox.

Lesley Stahl joined CBS News just in time to cover the Watergate scandal, and went on to become its White House correspondent for three Presidential Administrations. Since 1991, she has been a correspondent for “60 Minutes,” and has reported, in recent years, from Afghanistan, Rwanda, Taiwan, and Bhutan. Stahl is, with thirteen Emmy awards, the senior journalist at the most prestigious news program in television, and, as its owners move to placate the Trump Administration, she is witness to its moment of greatest peril.

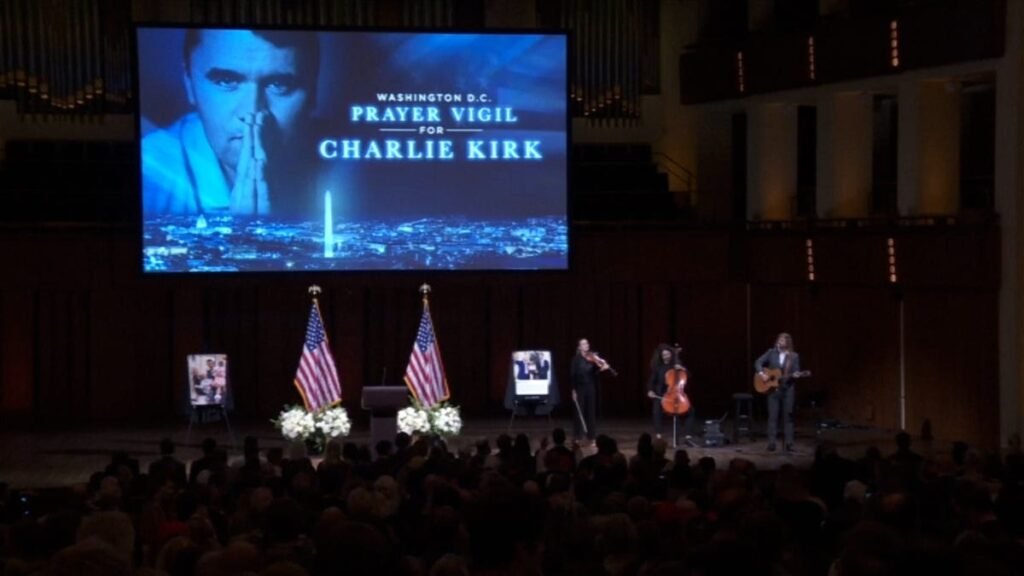

CBS is owned by Paramount Global. Paramount’s controlling shareholder, Shari Redstone, badly wants to merge the company with Skydance, an entertainment enterprise backed by one of the wealthiest people in the world, the pro-Trump software magnate Larry Ellison. The deal could bring her billions of dollars. One problem: Donald Trump has sued “60 Minutes” for twenty billion dollars. He and his legal team claim—to the derision of nearly all legal experts—that the program edited an interview with Kamala Harris in a way that somehow jeopardized his candidacy in the 2024 election. Rather than challenge Trump, Redstone wants to settle the suit, the better to soothe the President amid pending F.C.C. approval of the multibillion-dollar deal. On Wednesday, the Wall Street Journal reported that Paramount had offered Trump fifteen million dollars to settle, but the President’s team turned the offer down, insisting on at least twenty-five million, and an apology.

In recent weeks, both Bill Owens, the executive producer of “60 Minutes,” and Wendy McMahon, the C.E.O. of CBS News, resigned from their jobs, citing disagreements with corporate leadership. Among media executives, Redstone is not the only one who seems to be taking stock of her interests and deciding to accommodate the President rather than stand up for the journalists in her employ. Similarly, Jeff Bezos has made moves at the Washington Post that seem to cater to Trump’s interests and protect Amazon, the primary source of his fortune. The executive leadership of Disney, which owns ABC, settled a suit with Trump, who had been displeased with the way George Stephanopoulos had characterized his liability in the sexual-assault case involving the writer E. Jean Carroll.

On Memorial Day, I visited Stahl at her apartment on the Upper West Side to interview her for The New Yorker Radio Hour. Stahl is eighty-three and deeply attached to the network-news division where she has worked for more than a half century. While she was hyper-careful at times, insisting that “60 Minutes” was not in turmoil so much as it was under terrible pressure, it was clear that she was angry at Redstone and mourning in advance the potential demise of the program. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

You have been at CBS News for over fifty years. A good while!

Think about my pension!

It’s gonna be huge.

One hopes.

When you got to CBS News, Richard Nixon was in office. Pretty quickly thereafter, Watergate became a big story—for you, not least. How was CBS News run at that time?

Well, of course, we still had the “Edward R. Murrow Boys,” as we called them, people that he actually hired.

Edward R. Murrow, who covered the Second World War—“This is London”—and then became a symbol of integrity at CBS News.

Right. He set a standard for fairness, toughness, holding people’s feet to the fire. And I came in the third generation, let’s say, but still under the influence, and I was greatly affected by it. I think I still operate under what I learned when they hired me.

What were the lessons that you were learning?

Well, toughness comes to mind. The first thing was probably fairness and accuracy. But when you ask the question, the first thing I think of is that we were expected to ask tough questions and be a watchdog. My first story was Watergate. I was sent out because, frankly, I was brand new. I was an affirmative-action hire in 1972, and they sent me to cover Watergate because nobody thought it was a story. So, why not send the “new girl”?

Lesley, obviously we’re going to get to the present tense, and to the pressures on the press and CBS News and “60 Minutes.” But create a context here—how aware were you back then about the ownership of CBS News and the pressures that a President might put on the owners?

We were owned by William Paley back then. And fairly early on, when most of the television networks and most newspapers weren’t covering Watergate—it was the Woodward and Bernstein story—Walter Cronkite, our anchorman, decided that it was a very important story, and so he did a very long piece, fourteen minutes, which was more than half the broadcast. And if the piece itself didn’t make a statement, the length of it did. Walter’s voice carried a lot of weight. He was “the most trusted man in America.” And so that he did the story—they didn’t farm it out to someone else—also made a statement.

Well, the President of the United States picked up, or had his right-hand man pick up, the phone to call [William Paley], scream at him. I don’t know if you’ve ever had the White House scream at you. I have.

It’s no fun.

It’s terrible and frightening. And Paley succumbed. Let’s go back to the time when Walter ran the fourteen-minute piece. His plan was to do another fourteen-minute piece, which was in the works. Imagine that—that would’ve been twenty-eight minutes. Paley’s pressure was now so intense on the CBS news division that Walter was squeezed. He didn’t pull the piece, but he did cut it in half.

So Paley was no hero in this.

Paley was a hero during the McCarthy time, but not during the Watergate time.

Now, you’ve interviewed Donald Trump a number of times.

Four times.

When was the first time? How far do you go back?

Oh, the first time was when he became the nominee, right before his convention.

2016.

Yeah.

What was that like?

I interviewed him and Pence. He and Pence were sitting together side by side.

Mike Pence, his Vice-Presidential nominee.

Correct. And what was amusing was that I was focussed on their faces, and I didn’t see anything below their shoulders in my line of vision. But we had a wide shot. And in the edit room, we could see all three cameras going at the same time. And only then did I see Mr. Trump directing him with his hand, telling him when to be quiet, telling him when to talk. I thought that was hilarious.

But that first interview was, by the standard of Trump interviews, reasonably civil?